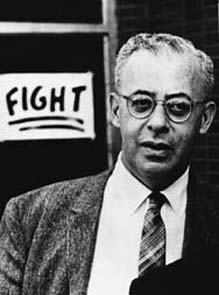

A recent poll asked conservative bloggers to name the most despicable men and women in American history. The top 25 villains included John Wilkes Booth, Benedict Arnold, Timothy McVeigh—and Saul Alinsky. A result like that might be dismissed as a fluke if it didn’t accurately capture the state of conservative demonology. Once little-known outside the ranks of community organizers he inspired, Alinsky holds a special place in the mind of the right: the central, secret influence behind the Obama Administration.

A recent poll asked conservative bloggers to name the most despicable men and women in American history. The top 25 villains included John Wilkes Booth, Benedict Arnold, Timothy McVeigh—and Saul Alinsky. A result like that might be dismissed as a fluke if it didn’t accurately capture the state of conservative demonology. Once little-known outside the ranks of community organizers he inspired, Alinsky holds a special place in the mind of the right: the central, secret influence behind the Obama Administration.

He is cited by name 226 times on National Review’s website alone. He’s made cameos in Mitt Romney’s stump speech. He is the thread that ties together President Obama’s Afghanistan policy, health-care reform, the media’s treatment of Sarah Palin, the stagecraft of the 2008 Democratic convention, and much more. Wherever Obama is portrayed as conniving, transparently political, a radical in moderate’s clothing, mention of Saul Alinsky is rarely far behind.

It’s tempting to laugh off the right’s Alinsky obsession, to place it next to Obama’s mythical teleprompter dependency as a piece of infuriating, if ultimately meaningless, conspiracy theorizing. But that would be too smug.

Just as conservatives were contracting their Alinsky obsession, liberals were getting over a remarkably similar obsession with our own intellectual bogeyman: the philosopher Leo Strauss. During the Bush Administration, Strauss featured on the left as the founder of a “cultlike” order of neoconservatives and ultimate source of the “noble lies” that launched the Iraq War. Last year, a Strauss-like character appeared as a hyperbolic advocate for the war in Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. The low point, however, was surely a 2004 play by Tim Robbins, which depicted an onstage cabal of neocons chanting “Hail Leo Strauss” and introduced this gem of a fabricated Straussian quote: “Moral virtue only exists in popular opinion where it serves the purpose of controlling the unintelligent majority.”

The similarities between the Alinsky and Strauss fixations can tell us a great deal about Americans’ conflicted relationship with intellectuals in politics, our common suspicions of the presidency, and how (and how not) to be a constructive opposition party.

The fixations do start from a kernel of truth. Alinsky did preach an influential brand of activism founded on realpolitik, not appeals to idealism: As he was fond of reminding his students, “You want to organize for power!” Obama practiced and taught Alinsky’s methods as an organizer in Chicago; Hillary Clinton made Alinsky the subject of her undergraduate thesis. On the other hand, a well-connected network of Straussians (including William Kristol; Paul Wolfowitz, a former student; and Abram Shulsky, a Strauss scholar who led the Bush Pentagon’s Office of Special Plans), rose high in neoconservative circles. A number of liberal thinkers, such as Alan Wolfe, managed to intelligently explore Strauss’s influence without descending into hysteria.

In their partisan parodies, however, both thinkers are painted as masters of deception, authorities who bless lies of every kind. References to Alinsky or Strauss may add an empty show of intellectual sophistication to the usual talking points, but they can almost always be crossed out with no damage to the argument. In one typical case, an Obama critic uses a mention of Alinsky to make the mundane sound sinister: “An Alinskyite’s core principle is to take any action that expands his power”—as if all politicians aren’t concerned with expanding political capital, and as if Alinsky himself were out for nothing more than personal power. On the other side, the last decade saw claims that Bush’s habitual use of terms like “regime” and “tyranny” were directly traceable to Strauss’s influence. But that’s hardly proof that Bush was invoking an entire philosophy every time he used those words.

As entertaining an exercise in self-righteousness as it can be, the search for hidden influences is a distraction from an opposition party’s strongest possible case. Liberal complaints about esoteric Straussians were themselves an esoteric exercise, and they did little if anything to strengthen the case against war. Inflating the power of sinister thinkers behind the throne is not just anti-intellectual. It turns the thinkers in question into flat caricatures and wipes away the complexity that makes any thinker worthy of the name—ignoring, for instance, that Alinsky was a strong critic of “big government” from the perspective of bottom-up organizing, or that Strauss was deeply skeptical about America’s ability to promote democracy abroad. The image of two Jews exerting a shadowy power over the powerful also plays into some uncomfortable stereotypes.

So why does searching behind the throne feel so necessary to so many? I’d argue that it has to do with a sense that our leaders are unaccountable, that the decisions that matter are made somewhere out of sight, subject to pressures we can see only hazily. Sometimes this sense is unjustifiable (today it has a good deal to do with the conviction that President Obama is an alien Other), and sometimes it’s more grounded in reality—but as long as it persists, the party out of power is going to be tempted to fixate on similar villains.

The next time around, progressives ought to resist that temptation. There’s nothing wrong with seeking to understand the forces that shape a would-be president’s habits of thought. There’s been valuable (and frightening) work done in this regard for Republican candidates from Rick Perry to Michele Bachmann. But the search for influences goes too far when it makes every other decision or tic of speech the product of some invisible mastermind or other, and when the mere mention of that figure’s name is enough to generate hisses.

On a pragmatic level, giving in to the temptation would do little to strengthen progressives’ cause, especially when we should be working to make the presidency more accountable in areas such as war-making powers and civil liberties, rather than responding to a sense of unaccountability by pointing to hidden influences with little effect. And on a principled level, progressives don’t need to parse the hidden motives or private philosophies of presidents and their circles; we ought to argue public policy on its merits, on its real effects on the Americans we want to speak for. That is, after all, our best case.

Photo Credit: Floyd Brown

Click to

View Comments