If taxes, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, are the price we pay for civilized society, what are we to make of the ever louder, ever more powerful anti-tax brigades who see opposition to taxation—any taxation—as patriotic obligation? As progressives, we disagree with them. We believe that society has a price, and it’s one we’re willing to pay. But no matter how tempting it may be, we can’t stubbornly hold fast to our position without acknowledging that there is something to the anti-taxers’ critique. The tax system is arcane and needlessly complex, a Byzantine maze that even the Treasury secretary had trouble navigating. As a result, government has become akin to a distant relative—one whom you hardly know, who shows up routinely with his hand outstretched, asking for a donation.

But while the anti-taxers have diagnosed the correct problem, they’ve prescribed the wrong solution. Rather than simply demanding tax cuts—or hikes, for that matter—we can work to open the tax system up, to show taxpayers how it works and where their money goes. In the process, we might be able to change the discussion around taxing and spending, making it less ideological and more relevant to the challenges of our day. Presumably, Americans will never like paying their taxes. But with the right policy proposals—and with their implementation—they might not despise doing so.

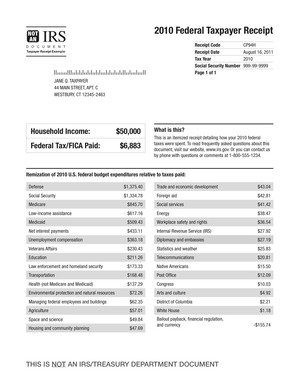

The authors of this piece have discussed one such proposal in the past (“Can’t Wait ’Til Tax Day!,” Democracy, and “A Taxpayer Receipt,” Third Way Idea Brief). We believe that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) should release personalized receipts to every individual taxpayer. With this article, we intend to fill in the details, to show how and why our proposal should become reality. The receipt would be straightforward enough: Individuals would receive them each year they file. This receipt would display services rendered and break out costs depending on the amount you paid. For simplicity’s sake, the receipt would be no more than a page long. Additional details would be available on an IRS website, the address of which would be located at the bottom of the receipt.

The reasoning behind such a receipt is equally straightforward. The businesses with which Americans interact everyday provide receipts for a wide array of transactions; some even offer to eliminate the charges if their employees forget to give you one. No matter if you’re buying coffee to get through the morning, or a new minivan to take the kids to soccer practice, the logic is the same. The receipt proves what you purchased and how much you paid for it. It tells you bluntly: You paid X, and you got Y. Clear as a bell.

Yet the government gives people no such receipt for the many services it provides them, leaving its citizens in the dark about what it does. A well-structured, well-designed receipt would clarify to taxpayers where their money is going, disabuse citizens of many popular misconceptions about taxing and spending, and help restore a modicum of trust between citizens and their government. As the IRS’s official taxpayer advocate, Nina E. Olson, recently said in a report that recommends Congress adopt the receipt, it “would help make taxpayers more aware of the connection between the taxes they pay and the benefits they receive.”

The Receipt

To create the receipt, we had to rely on only basic math. Displayed is each item’s percentage of the federal budget multiplied by the amount a person pays in taxes. For example, in fiscal year 2010, the Department of Veterans Affairs had a budget of $124.6 billion out of a total federal budget of $3.721 trillion, or 3.3478 percent. A median household pays $6,883 in income and FICA taxes. Calculating 3.3478 percent of $6,883 yields $230.43—the amount a median household paid in taxes that went to fund the VA.

The receipt would use cash accounting rules to keep it simple. As such, it would reflect only the spending in the government’s budget for a given year. It would not list the amount of the deficit and debt, but it would list annual interest payments on the debt. Similarly, it would not show the fiscal obligations for future Social Security payments, but rather the current payments for Social Security. Trust funds for programs like Social Security and interstate highways would be treated as having a single, aggregate source of revenue despite their dedicated taxes. That is consistent with cash accounting rules and the imperative to keep the receipt both simple and informative. The receipt would also show programs that are putting money back in taxpayers’ pockets, such as the 2008 bank bailout, which has been returning money to the government as banks pay back the taxpayer funds used to rescue them.

The key to a successful receipt is making it customer-friendly. This means highlighting well-known programs and agencies such as Social Security and the VA. It also means avoiding jargon; phrases like “domestic discretionary spending” are part of the lingua franca of budget wonks, but don’t mean a thing to most people. As we discovered while designing the model receipt in this article, conflicts between depth and length are inevitable. Anything more than one page will be overwhelming, but anything too compact will fail to be sufficiently illuminating. Our goal is not simply to replicate the entire federal budget for every taxpayer, but to distill it into useful information. The amount paid for specific agencies is more interesting than broad categories (e.g., the FBI vs. law enforcement). But listing only specific items will produce an excessively large “other” category. No one will trust a receipt that appears to be obscuring government spending.

Such conflicts could be resolved relatively easily by making more information—the unabridged version of your receipt—available on the Internet. Taxpayers should be able to access their receipt online, and then burrow deeper into the areas of the budget that interest them for one reason or another with the click of a mouse. Any taxpayer who files a tax return electronically could receive an email version of the receipt with links to more details. Of course, a printed version would still be necessary for the millions of Americans who file by mail. As with the rest of this proposal, all the requisite data are available, just waiting to be presented to the taxpayers.

In her recent report, Olson noted that a receipt would be “relatively easy to generate.” But politicians, as we know, excel at mucking things up. Any of the decisions related to the construction of the receipt—whether it is about the accounting method or how to characterize spending on controversial issues such as war and welfare—would be fraught with rampant opportunity for political manipulation. A receipt designed to advance the progressive agenda could, for instance, use categorization techniques to overemphasize the defense budget while minimizing contributions to Social Security; conversely, a receipt created by conservatives could do the same by labeling welfare payments in some way to demonstrate maximum offense.

Indeed, there is social science literature on the effects that different descriptions of policies have on public support. Although this “framing” problem could never be entirely eliminated, it could be minimized by lawmakers from both parties agreeing in the legislation on a set of categories for the receipt. Anything less than an upfront political agreement—something that the IRS by itself could not accomplish—would subject the receipt to partisan feuds after changes in power. Although an occasional revisiting of the receipt categories would keep it up to date, the receipt will fail if it is reduced to a political football. It must be widely seen and accepted as a good-government product, above the petty partisan squabbles of the day. We believe that the categories in the sample receipt displayed in these pages—which include Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, military personnel and procurement, and foreign aid, among others—are accurate, nonreductive, and nonideological representations of budget reality.

Our emphasis on a balanced set of categories should not be misinterpreted to mean that we don’t expect citizens to bring ideology to their receipts. Of course they will. Liberals, conservatives, and centrists will certainly have this or that to complain about. We’ll never be spending enough for some; we’ll never spend too little for others. The receipt, however, will bring such arguments closer to reality. By issuing receipts, the government would be demonstrating its trust in taxpayers to sift through the propaganda, look at the facts, and develop informed opinions. Evidence, as opposed to unsubstantiated assertion, would rule the day. The cost? For each taxpayer, about the price of a first-class stamp. Or less: Taxpayers who file electronically—about two-thirds of all returns—would receive a receipt by email. The information, after all, already exists. Additional administrative costs are likely to be minimal.

Political Consequences

With a well-designed receipt, myths and misconceptions about taxing and spending that refuse to die would be met with a mortal blow—and, we hope, replaced with more sober arguments that better acknowledge how complicated our politics can be. For instance, the idea that most of your tax money goes overseas, in the form of foreign aid and goodies to other countries, is a favorite trope of the anti-taxers. Why should we spend our hard-earned money to fix other people’s problems? asks this line of thinking. The thing is, it isn’t true; as the model receipt shows, the amount the federal government spends on foreign aid, narrowly defined, is remarkably small, about $43 a year for a typical taxpayer. We spend a good deal more every year on, say, law enforcement and homeland security.

Such myths gain purchase because the federal budget, such as it is, lacks immediate political salience. Consider the recent fight over health care. The Obama Administration tried to paint its reform effort as a way to bring down skyrocketing costs. Lawmakers and officials deployed a flurry of charts and graphs to make the point that costs had gotten out of control. Yet the idea never took hold in the public’s mind. This dynamic repeated itself only recently, when the recommendations of the President’s budget commission went down not in flames, but with a collective yawn. Simple facts about government spending were viewed as too distant and too abstract to make much of a difference in one’s policy preferences. A receipt would be a way of increasing public knowledge for everyone. By filing her federal tax return, the median taxpayer pays $1,355.13 for health-care programs that are both federal and state-based. Should we spend more? Or should we spend less?

Related questions would likely be asked about the amounts spent on Social Security and the debt. Given the heated political rhetoric surrounding the issue, the average contribution to the net interest payments on the federal debt—about $433.11—seems somewhat small; the amount the average taxpayer contributes to Social Security—$1,375.40—is higher. Do these numbers need to be adjusted? And, if so, how? Again, there would be many answers to such questions. But the ranks of those providing answers should not be limited to the expert, the wonk, and the political junkie. With the receipt in hand, all taxpayers would be capable of giving their own answers.

At first, the receipt would reflect a messy, chaotic government, with redundancies and inefficiencies clear to any taxpayer. Eventually, however, the receipt might act as a natural feedback mechanism, changing the reality it is charged to reflect. There’s wisdom in the old saying: Sunlight really is the best disinfectant. Some of the worst excesses of government spending would be curtailed, one imagines, in response to citizen anger about what was visible on the receipt. Likewise, government programs currently underfunded but widely liked might receive additional boosts of funding. NASA, for instance, regularly receives the type of broad public support rare for federal agencies in Gallup polling, but is not as well funded as one might expect. And the erosion of myths about what government does would also have serious implications, adding substance to debates where now little can be found.

Over the long run, a receipt would have the effect of more closely aligning citizen preferences and policy outcomes, a fundamental goal of any democracy. On occasion, progressives and conservatives alike might not find these outcomes to their liking. Yet no matter your ideology, it would be hard not to cheer the increases in public knowledge and accountability that a receipt would leave in its wake.

The political philosopher John Rawls once wrote: “The public political culture is bound to contain different fundamental ideas that can be developed in different ways. An orderly contest between them over time is a reliable way to find which one, if any, is most reasonable.” It almost goes without saying that we’re a long way from living up to that standard. Politics today are chaotic and deeply unreasonable; some of the loudest participants are the worst offenders. A receipt won’t reveal any final answers to great debates—it will be less a blueprint and more a point of departure. However, were it to be enacted, we hope that the ideal of reasoned debate it seeks to elevate could inspire the rest of our politics.

Click to

View Comments