In 1994, while the debate about President Clinton’s health care reform proposal was swirling, John Breaux, then-senator from Louisiana, was famously approached by a woman at an airport who demanded that he “not let the government get a hold of my Medicare.” Breaux, ever too polite, replied that he wouldn’t “let the government touch your Medicare.”

In 1994, while the debate about President Clinton’s health care reform proposal was swirling, John Breaux, then-senator from Louisiana, was famously approached by a woman at an airport who demanded that he “not let the government get a hold of my Medicare.” Breaux, ever too polite, replied that he wouldn’t “let the government touch your Medicare.”

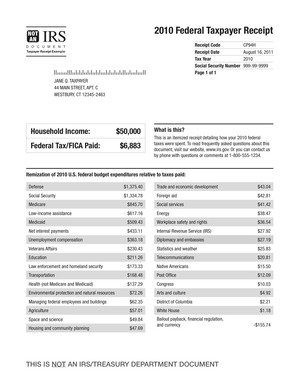

I thought of this story while reading John Sides’ description of his survey on the taxpayer receipt. At first glance, for those of us who’ve long championed the idea, the results were none too encouraging.

According to Sides, the receipt has essentially zero impact on whether one thinks his or her taxes are too high, nor does it make a dent in perceptions of public waste. Apparently, it doesn’t even influence what programs one prefers over others. The number of people who want to cut military spending and tax the wealthy, for example, remain roughly the same, regardless of exposure to the receipt. Sides himself seemed slightly taken aback by the severity of his results, writing, “It is perhaps surprising that the receipt had such small effects in this experiment, given how little many Americans know about how the government spends its money.”

But it is precisely how little Americans know about government spending that explains why the receipt had such small effects in the experiment. As the Breaux anecdote illustrates, there are some deeply entrenched beliefs—and misconceptions—in this country about what government does. Sides’ survey, meanwhile, functioned by showing people the receipt and then measuring their opinions. But the public has been shaped by decades of harsh anti-tax and anti-government rhetoric. To expect one document to undo the effects of that rhetoric all at once is asking too much. When the Obama Administration released its own version earlier this year—albeit online, and not via postal service—politics was not upended. Is it too much to hope that, over time, a receipt sent to every taxpayer might still have an impact?

I emailed Sides about this, asking him if, over a longer period of time, the receipt might make more a difference. He was gracious enough to respond:

That’s a good question, and it certainly points out a weakness of my little experiment. My guess is that the taxpayer receipt would need to be coupled with a sustained set of messages from political elites that emphasized the actual distribution of government spending. This is because I’m not sure how many people would actually read and process the receipt, even if it were provided annually over several years.

For the most part, I agree. The receipt, by itself, is no cure-all for the many ills of American politics. It won’t send everyone rushing to the progressive side. To change people’s minds about taxes and government, certainly other initiatives would have to be undertaken. But, contra Sides, they wouldn’t all have to come from the elites.

And thanks to the receipt itself, they wouldn’t have to. A receipt would increase the number of facts in the hands of citizens. This is no small thing. Our politics is diminished on a routine basis by fact-free arguments. It was only a few months ago that our loudest national debate concerned President Obama’s place of birth—as if there were facts in dispute. The debate we’re now having about the debt ceiling is similarly dominated by claims divorced from facts. If a receipt were mailed to every household in America for a sustained period of time, debates about taxing, spending, and the role of government would be more factually grounded than they are today. Those of us who support government and the taxes that fund it would be able to point to universally available evidence to make our arguments. Of course, those who believe otherwise would be able to do the same. Now, I tend to think that, when shown some basic facts, more people would find themselves in support of government spending, rather than against it. But even if I’m wrong, at least we’d be arguing about what government actually does.

It’s important to understand this in light of what Sides and I agree to be the best argument for the receipt: the increase in accountability it would make possible. Today, accountability is hard to come by; if one has preferences, identifying whether or not those preferences are being fulfilled means cutting through a haze of arguments devoid of facts. The receipt would make this task significantly easier.

A receipt wouldn’t solve everything, and its instant impact might be negligible. But given a bit of time to sink in, it would make for a more fact-based discourse and a more accountable government—worthy goals no matter what side of the aisle you’re on.

Click to

View Comments