The qualified defenses of Greg Abbott and Jade Helm paranoia are here, and while they’re less than persuasive, they are at least instructive. Whether offering partial justifications of fears surrounding the operation or simply dinging liberals for alleged hypocrisy, the rejoinders rely on replacing the operation’s actual opponents with hypothetical skeptics who are far more reasonable.

The qualified defenses of Greg Abbott and Jade Helm paranoia are here, and while they’re less than persuasive, they are at least instructive. Whether offering partial justifications of fears surrounding the operation or simply dinging liberals for alleged hypocrisy, the rejoinders rely on replacing the operation’s actual opponents with hypothetical skeptics who are far more reasonable.

Consider first Reason’s accusation of liberal hypocrisy, titled “I’m So Old, I Remember When Liberals Protested Military Exercises Conducted on U.S. Soil.” Taking note of opposition to a 1999 Marine training exercise by Bay Area locals, the magazine contends that “there might actually be some good reasons not to want a vast military operation in [the] neighborhood”—reasons that transcend the left-right divide and have nothing to do with tinfoil hats. Similarly, Austin-based Erica Grieder’s qualified defense in the Texas Monthly acknowledges the “lurid conspiracy theories,” but asks critics to consider “whether the community as a whole was being unduly conspiratorial, as opposed to reasonably curious.” There are plenty of reasonable concerns—about, say, noise and pollution—that have nothing to do with the advent of martial law. “Abbott’s announcement,” Grieder contends, “is apparently in response to such concerns, rather than those being fueled by the right-wing fear machine.”

Count me among the unconvinced. It’s impossible to know what was in Greg Abbott’s mind when he decided to monitor the operation, but in declaring that such monitoring would “ensure” that Texans’ “safety, constitutional rights, private property rights and civil liberties will not be infringed,” he all-but-suggested that they would be, if not for the diligence of his office. A different reading of his statement is plausible only if you ignore the context of swirling rumors and paranoia—all of which warranted a definitive rebuttal, an unmistakable message that there never has been any threat of invasion or martial law. Instead, Abbott’s statement conspicuously retreated from directly countering the conspiracy theories. The statement opens by referencing the “concerns of Texas citizens,” justifying its existence by erasing the distinction between legitimate concerns and kooky ones—or, more precisely, pretending that the latter simply don’t exist.

In a way, this move resembles what has taken place in the foregoing defenses. Both Reason and the Texas Monthly conjure up (or search conspicuously hard for) reasonable opponents and then imagine—at least in the Monthly’s case—that Abbott must have been speaking to them. This generosity (one might say credulity) is understandable among people who long for a responsible politics of government suspicion. (For one thing, it’s a major reason why Rand Paul gets the benefit of the doubt from certain mainstream voices, again and again and again.) The temptation to offer the most charitable interpretation explains the excuses and strained comparisons. (In the end, Reason offers no evidence that any left-wing politician dignified—even tacitly—whatever conspiracy theories accompanied the 1999 training exercise.) But to really bring about a non-loony conservatism, it would be far better in the long run to demand that leaders confront this stuff directly. The paranoia machine is real, it’s destructive, and it’s largely a conservative phenomenon. I’m certain Greg Abbott doesn’t agree, and I’m certain that he will never, ever say so. But he should.

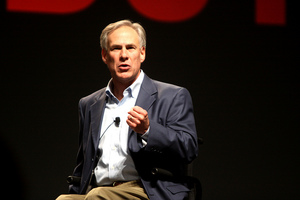

Photo credit: Gage Skidmore/Flickr

Click to

View Comments