Years from now, when the definitive history of American politics in the Obama era is written, some analyst will explain why conservatives, when faced with issues that were merely unfriendly, chose instead to make them unwinnable. Climate change is probably the chief example: Confronted with a problem that, on its face, seems friendlier to the environmental left, conservatives could have settled for a market-based solution (like cap-and-trade). Instead, they’ve launched a hopeless crusade against scientific consensus, one that can only end in ignominious defeat—while doing great harm to the planet in the process.

There’s a similar dynamic at work with current concerns over inequality and social mobility. Again, these are issues that don’t seem naturally hospitable to conservative policy priorities—but that doesn’t mean there are no ways for conservatives to address them. Josh Barro, for instance, has argued that conservatives should make peace with (and try to modify) redistributive policies that aren’t going to disappear anytime soon, and work to support more skills-based immigration. Even largely symbolic steps, like the “anti-cronyism” agenda associated with libertarian populism, at least amount to an admission that inequality exists and should be regarded as a problem.

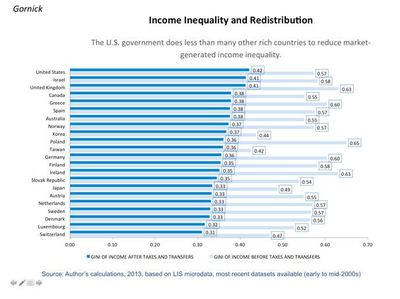

In this respect, Monday’s post from the conservative Manhattan Institute’s “e21” blog is somewhat perplexing. It’s occasioned by a recent speech given by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen entitled “Perspectives on Inequality and Opportunity from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” The response amounts, more or less, to: Why worry? Among other things, the post complains, “many analyses of income inequality use income before taxes are subtracted and transfers are added,” and these “are not realistic measures of inequality because top earners pay substantial taxes and low-income earners get transfers.” To wit: “the top 1 percent paid 35 percent of all federal individual income taxes in 2011, the latest data available.” That’s unsurprising: If the top 1 percent is capturing a large portion of the national income, of course it’s paying a large portion of the income tax. A far more interesting measure, featured here by John Cassidy, shows levels of inequality after taxes and transfers. Among all nations measured, the United States is somewhat unequal before taxes and transfers are taken into account, but it’s the most unequal post-taxes and transfers:

Another strange (if not unusual) quality of this piece is its breezy dismissal of the idea that anything can be done about declining social mobility. Income inequality is bad enough, especially because it translates into political inequality. But the prospect of the super-rich becoming a permanent class, a slightly different problem, makes inequality even worse. The consequences of social immobility are stark: The rich stay rich; the poor stay poor. Strangely, the post comes close to acknowledging this point: “Income inequality is only a problem if people cannot move up.” But then it veers off in a bizarre direction: “By some measures, America is the most unequal of modern industrial countries, but it is a magnet to millions of potential immigrants. Cuba or Russia with their more egalitarian societies are not attractive.”

I’m a little unsure what to make of this statement. Is the argument that among people who vote with their feet, the United States is a more attractive option than Cuba and Russia? Well, fine: that might count for something, although outpacing Cuba and Russia in terms of desirability doesn’t seem like much of an accomplishment. And of course, at some level, what immigrants think doesn’t really settle this question: Other things being equal, if social mobility were genuinely higher in Cuba or Russia, those places would present a more rational choice for immigrants trying to improve their lot in life. But most important, there’s that lingering suggestion that the price of relative equality is stagnancy a la the economies of Putin and Castro. Besides flying in the face of decades of evidence, this rhetorical shrug reveals an almost-despondent pessimism that anything can be done about a social problem of massive importance. In the long run, is that really wiser than facing up to the issue and trying to at least imagine a conservative response?

Click to

View Comments