The election of 2012 revealed a stark reality: Whatever may be the case in the states and congressional districts, the Republican Party faces deep difficulties at the national level. Many Republicans chalk this up to gaps in messaging and technology, to the selection of candidates who can’t fire up the base, or to what is for them the incomprehensible charisma of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Although a few Republicans are daring to go further, challenging party orthodoxy on issues such as immigration and same-sex marriage, they are a beleaguered minority. Most party leaders hope that cosmetic changes will be enough for the party to do better in 2016—without challenging the convictions of its core supporters.

The authors of this article have seen this movie before. A quarter of a century ago, in fact, we found ourselves with roles in it. In a 1989 manifesto, “The Politics of Evasion: Democrats and the Presidency,” (PDF) we debunked the views of our Democratic colleagues who hoped, as do so many Republicans today, that their fortunes would start looking up when a popular two-term President passed from the scene, and we laid out the kinds of changes the party would have to embrace if it wished to regain its competitiveness in presidential elections.

We were under no illusions that these changes would come without a fight. There was indeed a fight, but the changes happened, laying an enduring foundation for a stronger party. The narrative that follows helps explain why (as several reporters have told us) “The Politics of Evasion” is enjoying a samizdat revival in Republican circles.

Democrats in Disarray

In 1989, the Democrats were a party in trouble. They had just lost their third presidential election in a row, and prospects for regaining the presidency in the future looked dim. Holding onto control of the Congress permitted various party leaders—on the record and off—to continue to assert that things were not as bad as they looked. It all added up to, in the words of the country’s premier political columnist, David Broder of The Washington Post, “[t]he Democrats’ collective ability to deny the bleak reality of the present and past.”

In its post-election analysis, the party settled upon a catalog of explanations about what had gone wrong. Most of the recriminations focused on the Democratic candidate, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis. One pundit criticized his performance in the second presidential debate as showing “slightly less animation and personality than the Shroud of Turin.” Others focused on fundraising and technology, media and momentum. No one was very interested in talking about the issues or what the Democrats stood for, even though there was a mounting body of evidence indicating that the party’s problems were much deeper and more fundamental than the ones being discussed. As this systematic denial of reality stretched from 1988 into 1989, we realized, along with Al From and Will Marshall (founders of the reinvigorated Democratic Leadership Council and its think tank, the Progressive Policy Institute) that the Democrats were in urgent need of some reality therapy.

And so, in the summer of 1989, we sat down to write “The Politics of Evasion,” which the newly formed Progressive Policy Institute published that September. The essay was a frontal assault on three “myths” that Democrats had been using to explain away a series of dismal defeats. Our depiction of the party’s political standing was blunt: “Without a charismatic president to blame for their ills, Democrats must now come face to face with reality: too many Americans have come to see the party as inattentive to their economic interests, indifferent if not hostile to their moral sentiments and ineffective in defense of their national security.”

As is often the case when you set out to dispel cherished illusions, most of our fellow Democrats were not happy. For some years after, we were not very popular. The skunk at the garden party or the canary in the coal mine (choose your analogy) never is. There were, however, some important exceptions; notably, a young governor from Arkansas with presidential ambitions—Bill Clinton—and his allies in the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC). They took the findings of “The Politics of Evasion” to heart, and Clinton became the first Democratic President to win two terms in a row since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Today, nearly a quarter of a century later, the relative position of the two political parties looks very different, so it’s a good time to look back at our controversial essay. We’ll examine what we got right, what we got wrong, and the condition of today’s Democratic coalition. We’ll point out how Bill Clinton’s campaign and subsequent presidency successfully addressed the myths. Finally, we’ll assess the similarities and differences between the Democrats circa 1989 and the Republicans today, and draw on our experience to suggest some lessons for those seeking to reform the Republican Party.

Myths Debunked, Lessons Learned

“The Politics of Evasion” explored three myths that were prevalent among Democrats following the 1988 presidential election: the Myth of Liberal Fundamentalism, the Myth of Mobilization, and the Myth of the Congressional Bastion.

Liberal Fundamentalism

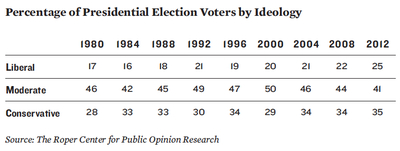

The Myth of Liberal Fundamentalism stated that “Democrats have lost presidential elections because they have strayed from traditional liberal orthodoxy.” Our argument was simple: This analysis was a myth because there simply were not enough liberals in the electorate to carry Democrats to victory—a reality that prevails to this day. The table below illustrates one of the more enduring patterns in American politics: Despite some liberal gains during the Obama era, conservatives consistently outnumber liberals, and moderates hold the key to victory in presidential elections.

Since 1989, the Democratic Party has moved away from the Myth of Liberal Fundamentalism and become a party that manages to attract moderates. In 1992, Bill Clinton ran as a “New Democrat.” He famously promised to end welfare as we know it, campaigned against outsized budget deficits and trade protectionism, and proposed to “reinvent” government, not expand it. By denouncing an obscure rapper named Sister Souljah who had made remarks about blacks killing whites (instead of other blacks), Clinton sent a signal to the electorate that he was not afraid to take on even the Democrats’ most loyal constituency. To the astonishment of many observers, African-American voters responded with overwhelming support. By his second term, some of them were referring to Clinton as America’s “first black President.”

Since “The Politics of Evasion,” Democratic candidates who succeeded in winning the presidency, Clinton and Obama, did so by holding on to liberals and attracting a substantial majority of the moderate vote. Clinton won 61 percent and 62 percent of moderates in his two elections; Obama won 60 percent and 56 percent of moderates in his two elections. The two losing Democratic candidates, Al Gore and John Kerry, won overwhelming numbers of liberals but did less well among moderate voters, with Kerry winning 54 percent and Gore winning 53 percent.

In the first decade of the new century, the Republican Party advanced a “base strategy,” under the guidance of strategist Karl Rove. As the table illustrates, this strategy was plausible for the Republicans, who in modern American politics begin every election with about one-third of the electorate in their pockets, but far more difficult for Democrats. Looking back at the Democrats’ four winning elections since 1989, it is clear that the Democratic Party is actually a moderate/liberal coalition party and not a liberal party—a positioning likely to yield positive returns in the years to come.

Further evidence that the Democrats have come to understand the Myth of Liberal Fundamentalism comes from a look back at Democratic primaries. Since 1989, the most liberal candidates running in Democratic presidential primaries have failed. Indeed, none of the aspirants who ran as the most liberal candidate in the field got very far at all. In 1992, Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa went into the race as a vocal New Deal Democrat. After winning his home state, his only other victories came in the Minnesota and Idaho caucuses. In 2000, former Senator Bill Bradley campaigned as the liberal alternative to Vice President Gore and was out of the race by Super Tuesday. The 2004 Democratic primary was filled with candidates who were more liberal than that year’s nominee, Senator John Kerry—from Howard Dean, who waged his race based on full-throated opposition to the Iraq War, to Senator John Edwards, who pledged a twenty-first-century war on poverty. In 2008, Barack Obama ran to the left of Hillary Clinton on Iraq but to her right on some domestic policies such as health care. In the end, there were not many substantive differences between them.

Had the Myth of Liberal Fundamentalism survived, subsequent Democratic primaries would have debated, among other issues, the welfare-reform act that Clinton signed into law in the summer of 1996. During the run-up to that historic event, passions within the party ran high over the wisdom of the emerging law. There was a highly publicized rift between Hillary Clinton and her mentor, Marian Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund, and the noisy resignation of three Administration officials, one of them Edelman’s husband, Peter. One might have expected this to be an enduring source of acrimony within the party. And yet, Bill Clinton was not subjected to a primary challenge from the left in 1996, and in November he ended up with 84 percent of the African-American vote and 78 percent of the liberal vote. In the middle of the 2004 nomination season (not the general election), Kerry even bragged about his vote on welfare reform. Today’s Democratic Party is a moderate/liberal coalition. Younger voters, who make up the heart of the Obama coalition, are more likely to be liberal and moderate than older voters, and far less likely to be conservative.

Mobilization

The second myth we explored was the Myth of Mobilization—the argument that “selective mobilization of groups that strongly support Democratic candidates, especially minorities and the poor, would get the job done for Democratic presidential candidates.” In the wake of Dukakis’s defeat, many Democrats claimed that if only more African-American or Hispanic voters had turned out to vote, the outcome would have been different. This was a testable proposition, so we set out to test it. “The Politics of Evasion” recalculated the 1988 Electoral College results based on three scenarios about African-American turnout levels—52 percent, 62 percent, and 68 percent of voting-age population (the last slightly higher than the record 66 percent reached during Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign). None of these turnout levels would have come close to changing the outcome in 1988. Under the first two scenarios, only Illinois and Maryland would have moved into the Democratic column, and under the third scenario only Illinois, Maryland, and Louisiana would have moved.

What was myth in 1989, however, has become reality in 2012. The nonwhite vote as a share of the electorate has expanded significantly, primarily because of disproportionately large increases among mixed-race voters, Asians, and Hispanics. In 1989, it was easy to see it coming; there was a large and growing Hispanic minority in America, and it looked Democratic in its voting behavior (although not nearly as Democratic as the African-American vote). The problem underlying the Myth of Mobilization was that at the time, most Hispanics could not yet vote: Many of them were too young, and many others were in the United States illegally.

On Election Night 2012, Republicans found themselves on the wrong side of a demographic tidal wave. Receiving less than one-tenth of the African-American vote was to be expected. More shocking was the party’s miserable performance among Latinos and Asian Americans, the two most rapidly growing segments of the electorate. And it will only get worse for them: By the middle of this century, the Census Bureau projects, whites will no longer constitute a majority of our population. In such circumstances, a nearly all-white party, which is what Republicans have become, would have no chance of obtaining an electoral majority.

In an analysis eerily reminiscent of “The Politics of Evasion,” Republican strategist Peter Wehner offers a dramatic calculation: “In 2012, Governor Mitt Romney carried the white vote by 20 points. If the country’s demographic composition were still the same last year as it was in 2000, Romney would now be President. If it were still the same as it was in 1992, he would have won going away. And if it were the same last year as it was in 1980, Romney would have won by a larger margin than Ronald Reagan.”

In short, the Republicans’ demographic problem is the mirror image of the one that Democrats faced a quarter-century ago. Back then there weren’t enough minorities to make the Democrats’ electoral strategy work; today, there aren’t enough whites to make the Republican strategy viable. The same long-cycle trends that gradually helped Democrats are now hurting Republicans.

The Congressional Bastion

The final misconception we called “The Myth of the Congressional Bastion.” This was perhaps even more important than the other two myths in sustaining the optimism Democrats felt about their future in 1989. It went something like this: “There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with the Democratic Party; there’s no realignment going on. The proof is that Democrats still control Congress and a majority of state and local offices as well.” We argued at the time that it was unrealistic to expect that the enormous Republican tide witnessed in Southern states at the presidential level would have no effect at the congressional level and that the power of incumbency was masking what was happening in the electorate.

Five years later that myth collapsed. In the 1994 midterm elections the Republicans won the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years. The House has been in Republican hands ever since, with the exception of the years 2007 to 2011. What “The Politics of Evasion” illustrates is that incumbency can protect a party against tectonic shifts in the electorate for only so long. The Republican hold on the House is not overwhelming, and it is far from permanent. If the generational replacement taking place at the presidential level continues, it will inevitably affect the congressional level as well.

What We Got Wrong

Overall, our 1989 analysis has held up pretty well. We did get some things wrong, however. In a section called “The California Dream,” we expressed skepticism that “[n]on-Southern gains [could] fully compensate for a Southern wipeout.” Today, that appears to be wrong—or almost wrong. In 2012, Obama lost all of the old South with the exception of Florida and Virginia, and in 2008 he lost the region except for those two states and North Carolina. In 1989, we thought that the Republican lock on the South would give them a long-term leg up in presidential races. We did not foresee an emerging Democratic lock on the Northeast and on the West Coast; nor did we foresee how changing demographics would turn previously out-of-reach states like Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida into contests that Democratic presidential candidates could in fact win. In particular, we could not imagine that California Republicans would mismanage the immigration issue so badly as to permanently antagonize the burgeoning Latino vote, moving that state firmly into the Democratic column. The Democrats’ California Dream of a generation ago has turned into a Republican Nightmare today.

We would be the last to deny that today’s Democratic coalition differs in important respects from the one that prevailed during the Clinton years. Latinos and Asians constitute a much larger share; so do highly educated professionals. And young adults, who trended conservative during the 1970s and 1980s, now vote Democratic in record numbers. If we had focused on the longer term, we might have glimpsed the demographic changes that John Judis and Ruy Teixeira were to highlight more than a decade later in The Emerging Democratic Majority. But we didn’t. We were determined to diagnose, and help cure, the ills of our party as it then stood after two decades of turmoil and decline.

Many things went right for the United States during the 1990s. Bill Clinton’s economic strategy—fiscal restraint, targeted public investments, openness to the world—helped usher in an era of balanced budgets and economic growth whose fruits were widely shared. The winding down of the Cold War allowed Clinton to reduce the military budget without being exposed to charges that he was soft on communism or weak on national defense, and his intervention in Bosnia proved that he was willing to use force in support of basic American values.

Surprising even the optimists, Clinton’s social policies contributed to a reversal of long-standing negative trends. Crime, drug abuse, and teen pregnancy, which had risen alarmingly in the late 1980s and early 1990s, peaked and began a long decline. These issues had been wrapped up in divisive racial politics for many decades. Clinton helped take them off the table, easing the way for the first African-American President. The Clinton years also saw the beginning of a debate about rights for gay and lesbian Americans. We had no idea, nor did many others, how rapidly this issue would move into the mainstream of American politics.

In short, by the end of the 1990s, many fewer Americans believed that the Democratic Party was inattentive to their economic interests, indifferent to their moral sentiments, or ineffective in defense of their interests abroad. To be sure, the Democratic presidential candidate lost the popular vote in 2004, when concern about terrorism and national security dominated the political landscape and the Iraq War had not yet become toxic. But by 2008, the American people were open to a new agenda—and to the unprecedented candidacy of Barack Obama.

The Republican Dilemma Today

The Democratic Party today is a party of moderates and liberals. It has a commanding lead among a new and very large cohort of young voters, a dominant position in the West and the Northeast, and improving prospects in the Rocky Mountain states, the Southwest, and a few Southern states. The strength of the party is such that, in 2012, Obama won a decisive re-election victory despite economic conditions that had historically doomed incumbent presidents. Today, it is the Republicans who face enormous political challenges.

As is often noted, the Republicans’ current problems are chiefly demographic. Consider young adults age 18 to 29. As late as 1976, voters in this age group leaned toward the Democrats. (Carter took 54 percent of their vote to Ford’s 46 percent.) During the 1980s, however, Reagan’s brand of conservatism proved enormously attractive to them. After fighting Carter to a draw among young adults in 1980, Reagan took 59 percent of their vote in 1984, about the same as his national vote. Running against Michael Dukakis in 1988, the decidedly uncharismatic George H.W. Bush still managed 53 percent, in line with his national share of the popular vote. As late as 2000, George W. Bush came within a point of equaling Al Gore’s share among adults under age 30.

Then the bottom began to fall out for Republicans. Although Bush received 51 percent of the popular vote in 2004, he garnered just 45 percent among young adults. In 2008, Barack Obama commanded an astonishing 66 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds, 13 points better than his overall national share of the vote. He did not do quite as well in 2012, but still hit 60 percent among young adults, 9 points better than his 51 percent national share.

Today’s young adults are the most diverse cohort—racially, ethnically, religiously—in American history, as Morley Winograd and Michael Hais pointed out in a prescient analysis of young people called Millennial Makeover, published in time to explain Obama’s first victory. Growing up taking this diversity for granted has made them instinctively tolerant on a range of social issues. The vast majority support immigration reform and cannot understand why there is even an argument about same-sex marriage. Even those who identify as conservative lean toward libertarianism on social issues, a fact that both Ron and Rand Paul have understood. For many of today’s young adults, environmentalism is a secular religion. These commitments collide head-on with the stance of the Republican Party, which stands today where Democrats stood in 1989—out of step with the mainstream on social issues. A party dominated by hard-edged social conservatives, opponents of the DREAM Act, and climate-change deniers will have a hard time gaining a hearing among the majority of today’s young adults.

Republicans’ problems with young adults may start with social issues, but they don’t end there. Eighteen-to-29-year-olds have experienced more than a decade of costly and controversial wars, and they are intensely skeptical about the wisdom of overseas military engagements—especially boots on the ground. They agree with the President’s call for “nation building here at home,” not only because they believe it has failed abroad but also because they see needs in their own lives—education and health insurance, among others—that government must help them meet. A greater share of young adults than older Americans favors a larger government that does more, and, as we saw, more of them are willing to self-identify as “liberal.”

It’s easy to think that these attitudes simply reflect larger numbers of immigrants and of racial and ethnic minorities in this cohort. The truth is more interesting. A recent survey conducted by the Brookings Institution and the Public Religion Research Institute found significant differences between younger and older white Americans as well—even within the white working class, a Republican bastion for much of the past generation. For example, compared with older cohorts, young white working-class adults are significantly less likely to see immigrants as threats or as taking away jobs from Americans, and more likely to believe that they are changing the country for the better. Fully 60 percent of white working-class millennials report that they have close friends born outside the United States, far more than their parents or even older brothers and sisters.

Young white working-class adults are far less likely to identify themselves as conservative or as evangelical Protestants, and far more likely to call themselves liberal and report that they are religiously unaffiliated. They support same-sex marriage by a margin of 74 to 22 percent, tougher environmental regulation by 63 to 35, and the DREAM Act, 64 to 33. There are generational effects, then, that transcend race, ethnicity, and immigrant origin and that bind this new cohort together.

In sum, millennials are different, and they are already having an impact on our politics. Among Americans 30 and older, Mitt Romney defeated Barack Obama by a narrow margin. But he lost young adults by five million, and with it the election.

The Republicans’ problem goes well beyond the overlapping groups of minorities and young adults. In recent years, the entire country has become more tolerant and inclusive. Majorities now support comprehensive immigration reform, same-sex marriage, and even the partial legalization of marijuana. In some of these areas, rank-and-file Republicans agree with the rest of the American people. But party leaders and elected officials have been slower to change, exhibiting a sort of “conservative fundamentalism” that is reminiscent of the “liberal fundamentalism” that afflicted Democrats in 1989. And like liberal fundamentalism, conservative fundamentalism stays strong largely because single-issue organizations and pressure groups remain adamantly opposed to majority sentiment.

The Republicans’ difficulties aren’t solely demographic, any more than the Democrats’ problems of the late 1980s and early 1990s were exclusively racial. Republicans’ policy dilemmas extend beyond social issues. Since the end of the Bush Administration, more and more Republicans have embraced the goal of shrinking government, using fiscal policy as the lever for the kinds of changes they want. When combined with the party’s long-standing opposition to new taxes, however, the new commitment to a balanced budget entails much deeper spending cuts than most Americans are willing to accept—especially in programs such as Social Security and Medicare. It’s easy to find surveys showing that Americans favor a smaller government that does less and prefer spending cuts as the principal strategy for achieving that end. But when survey researchers ask the obvious follow-up question—Which of the following programs are you prepared to cut?—the consistent answer is, just about none of them.

Nor have Republicans found a response to one of the dominant economic facts of our time—widening disparities of income and wealth. This is more than a distributional table in an academic study; it is a reality that Americans have noticed and don’t particularly like. A majority of Americans sees the GOP as a party that favors the rich and opposes every effort to make them shoulder a larger share of the revenue burden. President Obama scored a clean win over Mitt Romney on that issue, one of several reasons why Republicans were eventually forced to abandon the Bush-era tax cuts for higher-income earners.

The Republicans’ problem with the people isn’t just what they stand for; it’s how they stand for it. After decades of intensifying political polarization, a majority is tired of nonstop partisan fights, and support for a more cooperative politics of problem-solving is rising. In recent surveys, majorities of the people as a whole—and of Democrats and independents—have preferred elected officials who compromise to get things done rather than those who stand on principle. Among Republicans, however, it’s just the reverse. It was this sentiment that led Republicans into their confrontation with Obama over the debt ceiling—a public-relations fiasco from which they have yet to recover. Today, Americans are more likely to blame Washington gridlock on congressional Republicans than on congressional Democrats or President Obama. Unless far-sighted Republican leaders can persuade the party that uncompromising adherence to minority views is a formula for defeat, the party will continue to pay a steep price in the court of public opinion.

The Bottom Line: The Electoral College

A quarter-century ago, it was Democrats who had to thread the needle to win a majority of the electoral votes. Today the reverse is true, because Democrats begin each presidential contest with a significantly larger Electoral College base. During the past six presidential elections, Democrats have won 19 states (with a total of 242 electoral votes) all six times, and another three (with 15 electoral votes) five out of six times, for a total of 257. Republicans can counter with 13 states totaling 102 electoral votes that they have won six times, five states totaling 56 electoral votes that they have won five times, and six states with 48 electoral votes that they have won in the four elections since Bill Clinton’s presidency. (We include them in the Republican base because they are all Southern and border states for which Clinton had a distinctive appeal that future Democratic nominees are unlikely to equal.) With that stipulation, Republicans begin each presidential election with a base of 206 electoral votes, 51 fewer than do Democrats (and remember, the Democrats’ 257 total puts them just 13 votes shy of the needed 270).

Even more important, our tally of each party’s base leaves only five states unaccounted for: Colorado (9 electoral votes), Nevada (6), Florida (29), Ohio (18), and Virginia (13)—the super-swing states. Unless the Republicans can somehow pry states away from the Democratic base, they must win all three of the large super-swings (Florida, Ohio, and Virginia), while Democrats can prevail by winning any one of them.

This list of super-swings dramatizes the importance of the Latino vote for the future of the Republican Party in national elections. Latinos constitute 21 percent of Colorado’s population and cast 14 percent of the state’s vote in the 2012 presidential election. They are 23 percent of Florida’s population and cast 17 percent of the state’s vote in 2012. And in Nevada, they represent 27 percent of the population and 19 percent of the 2012 vote. The Latino share of the vote in these states—and nationally, where it represented 10 percent of the total in 2012—is bound to rise in future elections as more and more young Latinos reach voting age.

Reforming Political Parties: Some Lessons Learned

As veterans of an eight-year struggle to reimagine and reinvent the Democratic Party, we look at today’s Republicans with a wry sense of recognition. Much of what we wrote about our party a quarter of a century ago applies with only minor modifications to the contemporary GOP: an unattractive message, outdated policies, adverse demographics, and a fatally flawed political strategy, among other similarities. Now as then, the losing party is talking to itself more than it is listening to the people. Now as then, a party wrestling with defeat is hampered by an entrenched base that resists change and punishes those who try to bring it about.

In our experience, successful reform of a political party requires a number of difficult steps: diagnosing the party’s ills; discarding backward-looking policies; restating the party’s principles in terms that attract rather than repel skeptics; and crafting proposals that address the broad population’s problems and concerns, not just those of core supporters. Reform requires, as well, an organization that serves as a focal point for reformers, helps incubate new ideas, and leads the battle for their adoption by the party. And it requires, finally, standard-bearers who understand the reform agenda and can explain it clearly to party leaders, to the rank and file, and ultimately to the entire electorate. Money, technology, and tactics matter, of course, but only within a broader reform strategy.

Judged against this template, the reform of the Republican Party is taking, at most, its first halting steps. A politics of nostalgia still attracts too many Republicans, for whom “Back to Reagan” is a mantra that soothes and cures. But we are as far away from the end of the Reagan Administration as Democrats were from FDR at the beginning of the Nixon Administration. Reaganism applied conservative principles to a specific historical situation. If Reagan reappeared today, his principles would be the same, but many of his proposals would not. As long as Republicans imagine that the party’s 1980 platform will solve either today’s public problems or their own political problems, they’ll continue to struggle.

Another popular but counterproductive tendency is to blame the messenger rather than the message. Throughout the New Deal, Republicans convinced themselves that Franklin Roosevelt was a snake charmer who had bewitched the people and that all would be well once he passed from the scene. It took Harry Truman’s unexpected victory over Tom Dewey to convince Republican leaders that their problems went deeper, setting the stage for Eisenhower’s successful battle against Robert Taft. Ike’s program of “Modern Republicanism” ended the party’s battle against the New Deal and restored it as a serious national competitor.

Reagan was to Democrats as FDR was to Republicans—a great communicator whose rhetorical gifts sugar-coated a pill that they believed the people otherwise would not have swallowed. Not until Michael Dukakis’ startling defeat at the hands of George H.W. Bush did Democrats begin to realize that their problems might be more than cosmetic.

Once again, the same drama is playing itself out. Many Republicans (including their presidential nominee) believed up to Election Day that victory over Obama was assured. Recovery from recession was slow; unemployment remained high; household incomes were depressed; the President’s approval ratings hovered around 50 percent. As the returns rolled in, recriminations began: The wealthy Mitt Romney was miscast in hardscrabble populist times; he stood mute in the face of the Obama campaign’s summer onslaught; and he destroyed himself with his “47 percent” video, the economic equivalent of Todd Akin’s remarks on rape.

There is some truth to all this, of course, but it was mostly a diversion from the basic point: The Reagan agenda was played out, and the Tea Party’s Wahhabi-style drive to restore pure, uncompromised conservatism had led the party away from, rather than toward, an electoral majority. Tacitly acknowledging this reality, party leaders began to think out loud. While a report from the Republican National Committee focused mainly on mechanics, its authors forthrightly stated that “America looks different” and drew some obvious policy implications. In particular, they stated, “We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only.” The authors also acknowledged the force of generational change: “[T]here is a generational difference within the conservative movement about issues involving the treatment and the rights of gays—and for many younger voters, these issues are a gateway into whether the Party is a place they want to be.”

A subsequent report from the College Republican National Committee (CRNC) underscored this point. In findings based on two commissioned surveys and other data, the report documented the sizeable gap between young voters’ perceptions of the Republican Party and their own preferences and beliefs. While not ignoring problems rooted in technology and branding, the report paid the most attention to policy-based difficulties. While young voters’ reservations about the Republican Party begin with social issues such as same-sex marriage, they hardly end there. These voters also believe that the wealthy should pay higher taxes; that Republicans don’t want to help them pay their student loans; that reducing the size of “big government” is much less important than attacking entrenched interests on a broad front; that they will be better off under Obamacare; that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were mistakes that the United States should not repeat; and that, along with same-sex marriage, immigration reform functions as a “gateway issue.” Even when they disagree with Obama’s policies, most young voters at least give him credit for trying to fix problems, while Republicans are seen as mostly negative, often harshly so.

Toward the end of the CRNC report, the authors implicitly question their party’s dominant narratives. Their most recent commissioned survey compared a wide range of broad narratives that Republican candidates could use. The winners among young voters: creating jobs and economic growth, tackling the tough problems that will face the next generation, and giving hardworking people the opportunity to advance. The losers: protecting Americans’ liberty and the principles of the Constitution, promoting liberty and reducing the role of government, and protecting families and core American values. While the authors don’t spell it out explicitly, the conclusion is inescapable: The messages that have dominated the Republican Party since the beginning of the Obama Administration are turning off young adults. (The attack on big government is especially unpopular with Hispanics.) To summarize the report in language that its authors would surely reject, George W. Bush was more right than wrong, and the Tea Party is more wrong than right.

Reform on the Horizon?

In this context, it is hardly surprising that the party’s leading thinkers are beginning to weigh in. In an article entitled “Reaganism After Reagan” published in February 2013, National Review’s Ramesh Ponnuru commented, “Today’s Republicans are very good at tending the fire of Ronald Reagan’s memory but not nearly as good at learning from his successes. They slavishly adhere to the economic program that Reagan developed to meet the challenges of the late 1970s and early 1980s, ignoring the fact that he largely overcame those challenges, and now we have new ones.” Ponnuru concluded with a flourish that verged on heresy: “In his first Inaugural Address, Reagan famously said that ‘government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.’ The less famous yet crucial beginning of that sentence was ‘in our present crisis.’ The question is whether conservatism revives by attending to today’s conditions, or becomes something withered and dead.”

If “Back to Reagan” won’t do as a strategy and budget cutting has hit a political wall, what comes next? Since Romney’s defeat, several strands of conservative reform have emerged and gotten a new hearing. Rand Paul is trying to move libertarianism into the Republican mainstream, and recent controversies over drones and surveillance have given him the opportunity to enhance his national visibility. For conservatives, the road to reconnecting with young adults starts with libertarian-leaning stances on social and national-security issues.

Another brand of conservative reform tilts toward economic populism. A large piece of the Republican base has only modest levels of education and income. Mitt Romney had nothing to say to them, which helps explain why millions of white voters stayed home last November. Back in 2008, however, two young conservatives, Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam, had already diagnosed the problem. In Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream, they advocated the selective use of government to reweave the fabric of civil society and address the neglected economic needs of downscale Americans. Former Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty took up their cause under the banner of “Sam’s Club conservatism” during his brief 2012 campaign, but he could not channel the anger of Republican primary voters, whose antipathy to Obama spilled over into a general anti-government stance. Pawlenty’s candidacy quickly collapsed, but the woes of the working class remain, offering opportunities to conservative reformers willing to challenge entrenched economic orthodoxies.

A third strand of conservative reform, mainstream rather than populist, tries to build on what George W. Bush got right. In March 2013, two veterans of the Bush Administration, Peter Wehner and Michael Gerson, published a lengthy essay, “How to Save the Republican Party—A Five-Point Plan.” They began by noting key shifts in the country since Reagan: Demographic changes were working in favor of Democrats, and the end of the Cold War reduced the credibility of the classic Republican “tough on defense” stance. Echoing Ponnuru, they commented: “[I]t is no wonder that Republican policies can seem stale; they are very nearly identical to those offered up by the party more than 30 years ago. For [today’s] Republicans to design an agenda that applies to the conditions of 1980 is as if Ronald Reagan designed his agenda for conditions that existed in the Truman years.”

Gerson and Wehner went on to propose new approaches in five areas: focusing on the economic concerns of working- and middle-class Americans; welcoming rising immigrant groups; pushing back against hyperindividualistic libertarianism by demonstrating the party’s commitment to the common good; engaging social issues in a manner that is aspirational rather than alienating; and harnessing their policy views to the findings of science. While they aren’t always clear about the specific policy implications of these approaches, they do endorse breaking up the big banks and enacting comprehensive immigration reform. Describing opposition to gay marriage as a “losing battle,” they note tartly (and correctly) that “it is heterosexuals, not homosexuals, who have made a hash out of marriage,” and they suggest that Republicans and conservatives might more usefully focus on strengthening marriage in all its forms.

Gerson and Wehner offered not only policies, but a theme as well: “The Republican goal is equal opportunity, not equal results. But equality of opportunity is not a natural state; it is a social achievement, for which government shares some responsibility. The proper reaction to egalitarianism is not indifference. It is the promotion of a fluid society in which aspiration is honored and rewarded.”

If there were a political equivalent of intellectual property, we could sue for patent infringement, because these sentiments can be found, nearly verbatim, in numerous DLC documents from the late 1980s on. The resemblance is no coincidence: Along with Tony Blair’s New Labour, Gerson and Wehner cite the DLC and Bill Clinton as their models of successful party reform. Not surprisingly, we think they’re on to something.

Despite this intellectual ferment, the transformation of the Republican Party has barely begun. There’s no substitute for a leader with the guts to break with outdated party orthodoxy, as Clinton did on trade, fiscal policy, welfare, and crime, among other issues. And he did more than that: In the famous Sister Souljah episode, he spoke out against a tendency in the party’s base that crossed the line from protest to extremism. Mitt Romney and the other contenders for the 2012 Republican nomination had numerous opportunities to do just that, and they ducked them all. The incredible statements about women and rape by two Republican Senate candidates could have served as a Sister Souljah moment for Romney. But rather than using these to mount a full-throated protest against extremism in the Republican Party, he offered a mild rebuke that did nothing to undo the damage or to change the trajectory of the campaign. As long as aspirants for party leadership flinch from confronting their angry base, the American people will continue to see Republicans as an uncompromising, uncaring, and retrograde force.

And until party intellectuals are willing to go beyond policy prescriptions and call extremism by its rightful name, it is unlikely that any candidate will be willing to do so. The phrase “liberal fundamentalism” made us few friends a quarter of a century ago, but it was necessary for us to say it. We’re waiting for our counterparts among today’s Republicans and conservatives to do the same.

There’s something else missing as well—a focal institution that brings reformers together to craft new policies and the political strategies needed to make them effective, first within the party, and then for the entire country. So far, the Republican intellectuals seem to operate in a vacuum. They have little formal connection to the party’s elected officials or its organizations. It will be a sign of seriousness when Republican dissidents are willing to devote their energies and resources to creating an organization devoted to party reform and protecting it from being strangled in the cradle, as the defenders of entrenched arrangements will surely try to do. If Republican leaders and candidates try to improve their party’s fortunes without changing its orientation, they will surely fail.

Much is at stake, not just for Republicans, but for the entire country. The polarization of our party system has thwarted action on critical challenges and has exacerbated public mistrust. As long as our parties remain at roughly equal strength, our institutions can only work when adversaries are willing to debate fiercely—and then reach honorable compromises. A Republican Party dominated by a new generation of reform-minded conservatives who care more about solving problems than scoring points would be a huge step toward restoring a federal government that can govern.

Click to

View Comments